During

a savage eight-day stretch in the spring of 1983, I saw ten Jerry Garcia Band shows.

After rocking past the midnight hour, my companions and I drove back home every

night. I was a twenty-year-old squatter in my folks’ house, but they didn’t

seem to mind. Living on the road is hard traveling. Truckin’ back to your

parents’ house after every gig is pure lunacy.

My

descent into JGB madness began at the Bushnell Auditorium in Hartford,

Connecticut on May 29. The following night, we were back at the Bushnell,

courtesy of Doug, who was driving his mom's yellow Coup de Ville Cadillac. We were joined by Bob the

pirate, who was now known as “No Name Bob,” a nickname he earned after he lent

Doug a batch of sloppy boots: songs were misidentified, misspelled, and listed

out of order, performance dates were incorrect, vague, or nonexistent. “No Name

Bob” was born.

The

prospects seemed bleak for our ticketless trio. Saturday night, desperation and

depression deepened around the Bushnell. There were no scalpers in sight—just

Deadheads praying for the elusive miracle ticket. Suddenly, a door on the side

of the theatre swung open. There stood a smiling freak, and behind him, a

stairway to ecstasy. A bunch of us scampered up the carpeted steps like rats

making a late-night raid on Taco Bell. Presto! We were dancing in the Bushnell

balcony as Jerry ripped into “Mystery Train.” Doug charged into a

high-stepping, elbow-flapping polka dance. Nobody loves a “Mystery Train” bound

for glory more than Doug. “No Name Bob” smirked in admiration, for he’d never had

the pleasure of witnessing Doug under Jerry’s spell.

The

Bushnell shows whetted my appetite for the next tour destination—Jerry

off-Broadway. Anticipation boiled inside the Roseland Ballroom. On the last day

of May, New York City was juiced for a heaping dose of Garcia. Smoke billowed through

the ballroom—that exotic, aromatic mix of hash, ganja and cigarettes. A huddled

mass of hippies gathered close to the stage. The spacious ballroom floor was

surrounded by carpeted walkways and lobbies, and long, sleek bars from which

there was a golden glimpse of the stage. Wherever one lingered or roamed,

cocktail access was a cinch.

The

Bearded One appeared on stage in a red T-shirt instead of his customary

black—Summertime Santa. Garcia’s belly expansion was obvious, bordering on

obscene. He seemed to be adding ten pounds to his overburdened torso per tour. Melvin

Seals, and the new backup singers Dee Dee Dickerson and Jacklyn La Branch were

super-sized as well. This was a band that preferred a Grand Slam breakfast at

Denny’s over an aerobic session in Gold’s Gym.

Jerry

set sail with “Rhapsody in Red,” its rhythm and chord structure similar to “Let

It Rock,” its slick jazz lick jutting free—a deedle dee dee, a deedle dee diedle…

a deedle dee dee, a deedle dee diedle. Brightness vibrated from the

furious jam, ideas exploding inside a rhythm and blues container. Fortified by

funky organ-grinding, “They Love Each Other” playfully bounced in the second

spot. Garcia ignited a two-tier jam: round one, a reconnaissance mission; round

two, a searing solo that had the cosmopolitan hipsters howling their approval.

Garcia was en fuego, and his boisterous devotees knew it. Matters of the

heart ruled this set. Garcia blew the roof off the Roseland with diabolical

fret work during “That’s What Love Will Make You Do.” The remainder of the gig

was easy like Sunday morning, featuring a “Mississippi Moon” that made bikers

weep. Jerry’s tone was angelic:

“Honey,

lay down bee-side meeeee; angels rock us to sleeeep.”

I

reconvened with Doug at the Roseland bar after the show. The NBA Finals flashed

on a TV that dangled down by the single malt scotches. Doug’s favorite athlete,

Philadelphia 76ers Dr. J, was about to bury the Lakers. Dribbling near the

right baseline, the Doctor charged to the basket and soared to the sky. Laker

defenders guarded the hoop, forcing the airborne doctor behind the basket. Defying

the laws of gravity and comprehension, Julius reappeared on the other side of

the basket. And, with a casual flip of the wrist, the ball rolled from his fingertips,

kissed the backboard and swished into the net—apple pie à la mode—impossible,

but true. Philly had won the NBA Championship. Mere moments after “The Drive,”

a gaggle of security guards had to break up a ruckus between two lanky, but

rather violent, hippies, and a few of their associates. The gladiators left

behind a trail of blood. It was a grotesque conclusion to a righteous evening.

Back

in the black T-shirt for night two of the Roseland rendezvous, Garcia crooned

his mission statement: “I’ll take a melody and see what I can do about it; I’ll

take a simple C to G and feel brand new about it.” During “The Harder They Come,”

it felt like I was being checked into the boards of a hockey rink. The

temperament of the performance reflected the international chaos of the times.

Soviet-American tensions were peaking, Central America was a cauldron of

revolution (who can ever forget the Sandinistas?), and the Middle East was the

Middle East—no peace.

“Gomorrah,”

was an appropriate choice for a Hell’s Kitchen dance floor brimming with

whacked-out freaks gyrating to JGB—let the depravity and debauchery run wild.

Neighborhoods west of the Roseland were being terrorized by sadistic Irish

mobsters. The Westies instilled fear by ruthlessly chopping up their lifeless

victims and stuffing them in Hefty bags before depositing them in the East

River. Pimps, hustlers, whores and dealers saturated Times Square, and squadrons

of desperados loitered around the neon-lit sex shops. When Jerry sang, “Blew

the city off the map, nothing left but fire,” it sure sounded like prophecy.

And, to some extent, it was. The West Side of Manhattan circa 1983 has been

eviscerated. There’s nothing left but clean-cut capitalism and grimy greed.

In

the second half of the show, Garcia bullied four epic songs. If there was a

gadget that could tally guitar notes played per minute, the device would have

blown up. “Don’t Let Go” featured a twenty-minute instrumental during which I

chain-smoked three Marlboros. Gripping and terrifying, it was commensurate to

navigating through turbulent oceans on a starless night. Edgar Allan Poe would

have approved. It was a dark and stormy night,

wasn’t it?

The

crowd rejoiced for “Dear Prudence.” It came off as a tribute to Lennon because

we were only two and a half years, and less than one mile, away from where John

inhaled his last earthly breath. Garcia was the transformer, exploring layer

after layer of a tune that’s simply fetching, and quite strange in an elegant

way. The solo was outstanding, landing just short of the great Cape Cod

“Prudence” three nights earlier. “Deal” was a bloodbath! Garcia sang the song

as if he was discarding a bag of chicken bones, but the jam was an act of

acrimonious aggression. Garcia’s notes swarmed like agitated hornets around the

Jack Hammer bass and raging drums. When the set was over, it felt like the

Roseland had been ransacked and simultaneously healed—a mass exorcism. With

polarizing performances on successive nights, Jerry’s mosaic art mirrored the

passion and heat out on the streets of Manhattan.

Even

the Lord needed a day of rest, and so did JGB and the nuts that followed them.

The

tour resumed in Passaic, New Jersey, on June 3, 1983. While I was sucking brew

out of a pint in a seedy watering hole by the Capitol Theatre, a vaguely

familiar face approached and asked me if I needed doses. I wasn’t in the market,

but Doug was. The freewheeling acid guy, who I think I knew from community college,

looked like the Court Jester of Passaic, with his three-pronged joker hat and

tie-dye sweatpants. He handed me a vial of LSD and instructed me to dose my

buddy in the bathroom, $5 per drop. In the stall, I handed Doug the vial. He

proceeded to dispense three or four drops on his outstretched tongue. Things

were going to get real weird, real quick.

The

healthy crimson hue vanished from Doug’s mug. Beads of sweat rolled down his

pale cheeks. Probing waves of the mega-dose zapped his brain and rattled his

eyes. We fled the bar and stood on the street corner. Doug’s arms and legs

flailed wildly as he babbled gibberish. As nightfall descended upon Passaic, we

had issues. How was I going to explain this to his dad, Herb? When Doug jumped

into my Chevy that afternoon his future was bound for glory. The pride and joy

of the his clan, Doug was the heir apparent to his father’s law practice. I had

great respect for Herb and his wife Gloria. Though Herb never touched a drink

or smoked, he had a zany wit and a fiery passion for life, which he had passed

on to Doug. Herb also had a terrible temper; I could never explain to the old

man why his son was being returned home a comatose vegetable, unfit to tie his

own shoes.

My

other concern was the nature of the environment we found ourselves in.

Nighttime in Passaic was not conducive to psychotic episodes. What type of city

was Passaic in the early ‘80s? The summer before, I’d pulled into Passaic for a

JGB gig and found a spot a few blocks from the Capitol. Prior to parallel

parking, I discharged Laurie and Tracy, hippie goddesses, from my maroon

Caprice and told them to meet me in front of the Cap. A cop stopped the ladies,

asked me to roll down my window and hollered, “What? Are you fuckin’ nuts?

Letting theeeese girls walk by themselves, in this neighborhood!? Are you

fuckin’ nuts?!? And if you don’t move your car, you’ll be lucky to have a fuckin’

steering wheel left!”

So,

there I was, on the hostile asphalt of Passaic, trying to find a sanctuary to

nurse Doug back to sanity. I tried to lure Doug into the theatre, but his heart

was pounding for the emergency room. After the ER doctor examined Doug, he

assured us we had nothing to fear but fear itself. The good doc went back to

treating emergency room causalities. We went to see the Captain.

There

were two shows that night. We missed the early one and were tardy for the late

show. My buddy proved to be a resilient son of a bitch. He was getting off on

“Love in the Afternoon.” Psychedelics stroked the sweet part of his brain as

the calypso riffs rolled from Jerry’s guitar. I was almost jealous. I’d twice

missed my first live “Cats Under the Stars.” What I missed was irrelevant. I

was eternally thankful to be rolling up to his Doug's house with their pride

and joy intact.

Doug

weathered the mega-dosing, and after a few hours of psychotic sleep, we were

back on the trail of the Great Garcia. This time we were joined by my other

primetime touring accomplice, Perry. I’d met Perry in tenth grade during my

brief stint in Mr. Murphy’s geometry class. Perry was a soft-spoken, blonde-haired

Norwegian who wore a cappuccino-colored corduroy jacket and smoked Parliaments.

We crossed paths again a few years later at Rockland Community College and

experienced our first Jerry shows together at the Capitol Theatre in ’81. Perry

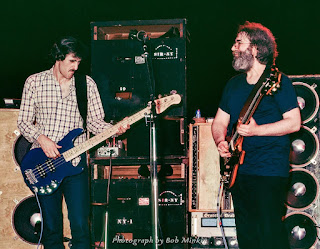

was coming into his own as the lead guitarist of the Roadrunners. They played a

whole lotta Dead and mixed in some Clapton, Hendrix, Dylan, Stevie Ray Vaughn,

Little Feat, and CCR. They didn’t have a distinctive voice at first, but

inspired by Jerry, Perry’s riffs and licks blossomed. The Roadrunners rapidly found

their niche as a roadhouse jam band, becoming popular in the pubs and saloons

of New City, Nanuet, Spring Valley, and Pearl River.

The

day following his LSD meltdown, Doug was tearing north on the endlessly winding

Taconic Parkway in his Coupe DeVille. I was riding shotgun, and Perry lounged in

the back. When you’re in the thick of a hedonistic marathon like this, the

actual day of the week becomes meaningless. Still, it was Saturday night, and

we were working our way back to JGB at The Chance in Poughkeepsie. As we drove

through historic Poughkeepsie and admired the Hudson River to our west, I

sensed the presence of Colonial America. I half expected to see Patrick Henry

on horseback galloping through the cobblestone streets.

The

Chance was a divine gathering nest for a JGB gig. Opened for business as the

Dutchess Theatre in 1912, this red brick building resembled just about any old

country barn and had a 900-person capacity. Closed from 1945–1970, it reopened

as Frivolous Sal’s Last Chance Saloon before officially being known as The

Chance in 1980. The charming Chance was a tiny ballroom, theatre, and bar

rolled into one. Such were the allures of a JGB tour. This front-porch atmosphere

was unattainable at Grateful Dead shows.

With

a long night and two shows ahead of us, Doug abstained from anything stronger

than a few bong hits. He moved close to the stage and waited, anxiously, until

the sweet twangs rang from Garcia’s guitar. Perry and I met up with his older

brother Stan and his friend Johnny at the bar. With a can of Budweiser

occupying one hand, I kept my other hand free to juggle joints, cigarettes, and

bullets of blow. When the red velvet drape was raised, the band was already playing

“Cats Under The Stars.” Smiling wildly and wearing sunglasses, Garcia began to

croon. A pleasantly pungent plume of marijuana smoke billowed through the

Chance.

“Hey,

Howie-baby!” shouted Stan. “Someone forgot to tell Jerry he’s at the Chance. He

still thinks he’s at Coney Island, sunbathing.” An eruption of laughter followed,

and nobody chuckled harder than the messenger. Eight years older than Perry,

Stan was built like a harpooner—broad, noble shoulders with a sloped stomach solid

as granite. Grinning, Stan pivoted towards me and showed me how to wail air

guitar left-handed.

With

his knees slightly bent, Stan assumed a sturdy stance, arms opened wide, palms

out, like a magician who had just plucked a rabbit from a bowl of chili. His

expression turned serious as he peeked at his fingers as they slid across an imaginary

fret board. Confidently strumming away with a bottle of Bud in his right hand, Stan

was amused by his own antics. Suddenly turning towards his best pal, Johnny,

Stan the Man went through the same shtick all over again. Digging the groove

all night long, Johnny was a lumbering figure with thick brown hair compressed

like a Brillo pad. Although he had a bouncer’s build, Johnny B. Goode had the

goofy vibe of a Merry Prankster. Peeling twenties from his cash wad, Johnny financed our Budweiser pipeline. He

had recently picked the winning numbers in the New York State Lottery; however,

he had the misfortune of having to share the $4,000,000 jackpot with six other

winners. After taxes, his cut was about $20,000 a year for twenty years.

When

the curtain was hoisted for the late show, JGB rocked “Rhapsody in Red.” “Sugaree”

was delightful to see; Garcia came off like a thousand turkeys gobbling in

unison. Every show on this tour had its shining moments. The “Midnight

Moonlight” encore had us prancing about like Russian Cossack dancers.

After

partying with reckless abandon for the duration of two shows, Perry and I were

sleeping soundly on the ride home as Doug drove south on the Taconic Parkway.

We were all awoken by the screeching sound of steel scraping steel. Doug

instinctively tugged the wheel to his left, steering us off the guard rail and

separating us from a gruesome tragedy in Hopewell Junction. Once again we’d

danced with death. If it wasn’t for a simple flick of the wrist, our Grateful

odyssey would have been terminated.

There

was a small dent on the yellow Coup de Ville—not the type of damage that would prevent

Doug from driving to Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, for two shows at the Tower

Theatre the following night. Enough was never enough—we had to keep on chasing

lightning. A state trooper ticketed Doug for speeding on the New Jersey

Turnpike. By the time we found the Tower Theatre and parked, we knew that the

early show had begun. We sprinted a 100-yard dash to the theatre door in

personal best times. For the third time on this tour we missed “Cats Under the

Stars.” I guess it just wasn’t in the stars. JGB was wrapping up “They Love

Each Other” as we strutted down the carpeted aisle. Garcia rewarded our

tenacity with the only “Let It Rock” of the tour, a tremendous version with a

pair of furious solos. That one “Let It Rock” made all the sacrifice

worthwhile.

As

for how Doug explained away the dent on the Coupe, I would find that out fifteen

years later, at his wedding. During the best man’s toast, Doug’s younger

brother, Eric, asked me to stand up and testify. In front of the entire Schmell

clan, I was asked to swear that we actually hit a deer that night coming back

from the Garcia show. I proceeded to perjure myself and kept the myth alive.

Herb was laughing so hard his yarmulke almost dislodged from his head.

This tale was adopted from Positively Garcia: Reflections of the JGB

This tale was adopted from Positively Garcia: Reflections of the JGB