BUSY

BEING BORN

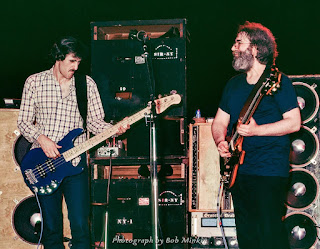

As Garcia, Saunders, Kahn, and

Kreutzmann launch “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry,” time’s

suspended by the hypnotic groove. It’s a Dylan tune, yet there are no lyrics to

ponder. The repetitive riff is sublime—Frisco Blues—as mysterious and vast as

the Pacific, yet heavenly and cool in the style of Miles. Garcia’s snapping

strings sing a lonely lullaby—poetry-in motion. The drummer and bassist are

locked in tight, and the beat bounces brightly as the earthy vibrations of the

Hammond organ swirl in and out and all around—aural ecstasy! This blues riff

will never sound this good again, and the musicians know IT. There’s a song to

be sung, somewhere down the line, but the band proceeds deliberately, intent on

basking in the moment. A modest studio gathering and a privileged West Coast FM

radio audience are listening in on this intimate musical conversation. Out of

the mesmerizing groove, a mellifluous voice suddenly whispers:

“KSAN in San Francisco.”

Ordinarily this type of interruption

would defile a masterpiece like a scar on the Mona Lisa, but the lady DJ sounds

sultry, and it seamlessly intertwines with the music as if it were preordained.

And if ever a radio station deserved to beat their chest, KSAN deserved props for

broadcasting this jam from Pacific High Studios on 60 Brady Street in San Francisco.

The musicians in the studio couldn’t hear the radio call letters, but Garcia is

seemingly spurred on as if he could hear the DJ’s titillating tones. With each

round, his leads become more pronounced and provocative. Garcia’s obviously an

inspired man, possibly possessed. Even the purest of archivists wouldn’t wish away

the KSAN interruption. It’s a stamp of immortality.

Jerry

draws a deep breath, steps to the mic, and an angelic voice fills the air.

“Wintertime’s coming, it’s filled with frost. I tried to tell everybody but I

could not get across.”

Hey,

Jerry, wrong verse…wrong lyrics! Garcia sings the third verse instead of the

first, and Dylan’s words are, “THE WINDOWS are filled with frost.” Yet we’ll

forgive this faux pas because the bearded guru is singing with feeling, sweet

and true. Without a trademark solo, Jerry transitions from the third verse to

the first:

“I

ride a mail train, mama, can’t buy a thrill.” Priceless. Garcia caresses every

syllable until the jingle nimbly touches down. Garcia will perform more complex

versions of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry,” but few satisfy

like this odd nugget which radiates in its own imperfection. If I were

commissioned to arrange a soundtrack for a documentary on the essence of Garcia

as a performer, this is where it would begin.

The band noodles and doodles in

preparation for the next entrée. Garcia has a thing for tuning up. It’s an

artistic endeavor for him, and quite frankly, the guy’s got a problem; he can’t

stop picking. Someone in the pocket-sized audience yells out a barely audible

request, and Garcia replies, “Everything’s gonna be all right.” Sure, that was

easy for Mr. Garcia to say. By 1972, he had the hip world at his command. With

the Grateful Dead’s most recent vinyl releases, Workingman’s Dead

(recorded in Pacific High Studios) and American Beauty, the

band had finally tasted commercial success and critical acclaim. The band’s

lyricist, Robert Hunter, was on the mother of all rolls, penning verse after

verse, and anthem after anthem, as if he were Robert Allen Zimmerman, the pen

master himself. And the twenty-nine-year-old leader of the band, Jerry Garcia,

was a virtuoso in his prime, unleashing visions and dreams beyond imagination.

With Kahn, Kreutzmann, and Saunders jamming by his side, Garcia glowed.

Everything’s gonna be all right, indeed.

Following Garcia’s proclamation, the band

slams into “Expressway To Your Heart.” All aboard the Motown Express! This

little ditty penned by Gamble and Huff, and made famous by The Soul Survivors,

is now a vehicle bulleting at the speed of sound—a bawdy traveling companion

for “It Takes a Train to Cry.” Garcia and friends hammer “Expressway” as if

this is the last jam of humanity. This tour de force rages down a jagged

highway, and the band never eases off the gas—ten minutes of thrills at

breakneck speeds. They interact as if they’ve sped down this road a thousand

times before; however, this is their debut gig as a quartet. Jerry defers to

Merl a few times, and Saunders drains a whole lotta soul from his Hammond B-3

organ. But on this number, Garcia’s driving the train, and it’s quite possible

he’s high on cocaine. His volatile playing veers off the tracks, yet the

Bearded One finds his way back home by balancing musical equations on the fly.

For

this Pacific High gig, Grateful Dead drummer Billy Kreutzmann, fills in for Bill

Vitt, who had handled drumming duties for most of the Garcia/ Saunders shows.

The familiarity of having Kreutzmann striking the skins is a rallying force for

Garcia, and it energizes the quartet as a whole. The first Garcia/Saunders show

took place on December 15, 1970, and after twenty or so performances, Garcia

and Saunders were bubbling like lava. Jerry had also been moonlighting with the

New Riders of the Purple Sage, but this involvement with Saunders and Kahn had

developed into his pet project outside of the Grateful Dead. With Kreutzmann on

board, this was perhaps the finest band of Bay Area musicians ever assembled.

These visionaries were on the same wavelength, speaking the same language; yet

there was virginal excitement in Pacific High Studios—a talented group hitting

it off on their first date.

On

the heels of such a fanciful Pacific High opening, “That’s a Touch I Like” is

no slouch in the third slot; in fact, it’s ravishing. After a crisp opening

solo, Jerry croons, “Red ribbons in your hair, I’m kind of glad that you put

them there. That’s the touch I like. That’s the touch I like. Whoa-oh-oh,

that’s the touch I like.” This snippet of female infatuation was penned by

Jesse Winchester for his eponymous 1970 album. On that record, this tune is mislabeled

as “That’s the Touch I Like,” and

that’s the touch Garcia likes, because that’s the way he sings it. Winchester

actually sang, “That’s a touch I

like,” and when his album was reissued on CD in 2006, the title was corrected.

Anyway,

those witnesses at 60 Brady Street must have been swept out of their seats. Garcia’s

charm and inquisitive nature took center stage. Is it the red ribbon, or the woman,

that sparks the singer’s imagination? Either way, Jerry’s so pleased, he

concedes, “I’ll be on my very best behavior.” The pulse and vibration of this

performance is infectious, an instant remedy for the blues.

In

arcane ways, these songs seem to be communicating with each other; each tune

has a companion. It begins with the traveling tunes, “Train to Cry” and

“Expressway.” The flipside for “That’s a Touch I Like” is this show’s encore,

“How Sweet It Is.” Written by the team of Holland-Dozier-Holland, and popularized

by both Marvin Gaye and James Taylor. “How Sweet It Is” would go on to be

immortalized by the Jerry Garcia Band, becoming their signature opener, and the

band’s most frequently played number. In substance and style, “How Sweet It Is”

and “That’s a Touch I Like” are siblings; yet, “That’s a Touch I Like” would

never be performed again after May 21, 1975. Of the two, I prefer Jesse

Winchester’s baby. It could have been a dynamite alternative opener to the

overplayed “How Sweet It Is.” However, on this night, both ballads are

rapturous, a snapshot of Jerry’s giddy optimism.

These

were also optimistic times for American culture. In February of 1972, two

cinematic classics, The Godfather

and Deliverance, were released, and Don

Mclean’s “American Pie” was number one on the Billboard charts. In matters of

war and peace, these were turbulent times. The United States was fatigued from

a decade of civil strife and the horror of the never-ending war in Vietnam.

Moving songs of protest, empowerment, and hope were replaced by monumental

escapist anthems and Teflon rock. Maybe music couldn’t change the world, but it

could take you to another time and place—transcendence. And in 1972, nobody was

improvising mind-bending guitar jams like Jerome John Garcia.

Back

in Pacific High Studios, Kahn kicks off “Save Mother Earth” with thick,

brooding bass blasts. Soulful riffs from Saunders ensue, and Garcia answers

with yearning guitar bursts. The only original played by the band on this

night, “Save Mother Earth” was written by Saunders for his soon-to-be-released

album, Heavy Turbulence, which would also

feature the following number, “Imagine.”

Garcia

must be donning Superman’s cape as he wails on “Save Mother Earth.” Captain

Trips breaks the instrumental free from the mother ship, spinning and spiraling

it to the cosmos and beyond—“Dark Star” > “Mind Left Body Jam” territory,

the psychedelic providence of the Grateful Dead. Jerry pecks away frantically

and the sonic voyage gets way out there—farther, further, faster. When the

exploration crackles, fizzles and fades, Saunders gently leads the band into

“Imagine.” The audience applauds the soothing familiarity of the melody, relieved

to be floating back towards earth. The segue is flawless. There’s no attempt to

sing Lennon’s song. Garcia’s guitar humbly and simply pleads for peace on

earth.

For

Deadheads who collected bootlegs prior to the proliferation of digitized music,

“Imagine” is the last song on the first side of a ninety-minute Maxell XLII

cassette tape. The tape from 2-6-72 is a perfectly balanced boot that plays

like an album. Sides A and B have their own distinctive mojo, and they

complement each other as if they are separate sets, although this is a

ninety-minute performance with no break. As the most bootlegged performer of

his time, Garcia seemingly had a sixth sense for filling up tapes, as if he was

performing especially for the tapers. This notion is not farfetched. In the

early ‘60s, Garcia bootlegged largely unknown and wildly talented bluegrass

musicians—the very troubadours that fueled Garcia’s

guitar picking fetish.

Side

B commences with “That’s All right Mama,” a four-solo pressure cooker—Beale

Street spirit meets New York City tenacity. Rolling Stone magazine

identified Elvis Presley’s recording of “That’s All right Mama” as the first

rock and roll record, and Garcia’s extended version embdies and amplifies that

rowdy/rebellious swagger. “One and one is two. Two and two is four,” sings

Jerry. Improvisation is like arithmetic in Garcia’s brain. The waterfall of

creativity flows from his guitar, yet it all makes sense; every note is a

number leading to the final sum. Transparency. When Garcia’s in the zone, he’s

like Einstein on bennies—in front of a blackboard, chalk in hand.

Lingering

in the Mississippi Delta, the band pairs “That’s All Right Mama” with Jimmie

Rodgers’ “That’s All Right,” a song that has been mislabeled on most Pacific

High Studio tapes as “Who’s Loving You Tonight.” The circulating KSAN tape is

missing the opening of this song and it’s a damned shame, because as we jump

in, Garcia’s on a rampage; his searing leads sizzle in agony. Saunders leans

into his Hammond and unleashes hissing, hell-bent blues, the nasty and

tenacious strain. As Jerry follows, he comes off like Clapton, Bloomfield, and

Stills all rolled into one, and as he finishes out this tribute he howls, “But

now that I wonder, whoo-ooh-ooh-ohh’s loving you tonight.” Somewhere in heaven,

Jimmie Rodgers yodels back his approval.

An

iconic album, or performance, is usually characterized by a magnificently

orchestrated selection of songs that relate to, and build upon, each other, so

that the listener is drawn deeper into the web of the artist’s vision. If you

hit a shuffle button and randomly listen to the songs of Abbey

Road,

the playback won’t create the same experience as if the songs were heard in

their rightful order, as consciously conceived by The Beatles and George

Martin. The songs still stand on their own, but their collective power

diminishes. Great live performances can be consciously orchestrated, but I

prefer the thrill of free-flowing improvisational genius, which under the right

circumstances, and fueled by the right momentum, can create a masterpiece that

exceeds what the performer or audience could have ever imagined. On 2-6-72,

Garcia is in that rarified air. After the Jimmie Rodgers’ stomp, Garcia paints

his masterpiece with Dylan’s “When I Paint My Masterpiece.”

“Oh,

the streets of Rome are filled with rubble, ancient footprints are everywhere,”

croons Garcia—admiration and awe blatant in his delivery. In Garcia’s world,

Dylan’s visions are glorified: Inside The Coliseum, dodging lions

and wasting time…I landed in Brussels, on a plane ride so bumpy that I almost

cried…Train wheels running through the back of my memory…Young men in uniform

and young girls pulling mussels…Newspaper man eating candy, had to be held back

by big police. Oh, the sights and sounds! In Dylan’s

studio recording of “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” the kaleidoscope of images

are stacked upon each other, almost too much to ponder in a single listen. In

Garcia’s “Masterpiece,” the tempo is relaxed, and the tone of his vivacious

vocals illuminates Dylan’s lyrics. The three wicked guitar solos give the

listener the time and space needed to relish and absorb the majesty of it all.

“Oh,

the streets of Rome are filled with rubble, ancient footprints are everywhere,”

croons Garcia—admiration and awe blatant in his delivery. In Garcia’s world,

Dylan’s visions are glorified: Inside The Coliseum, dodging lions

and wasting time…I landed in Brussels, on a plane ride so bumpy that I almost

cried…Train wheels running through the back of my memory…Young men in uniform

and young girls pulling mussels…Newspaper man eating candy, had to be held back

by big police. Oh, the sights and sounds! In Dylan’s

studio recording of “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” the kaleidoscope of images

are stacked upon each other, almost too much to ponder in a single listen. In

Garcia’s “Masterpiece,” the tempo is relaxed, and the tone of his vivacious

vocals illuminates Dylan’s lyrics. The three wicked guitar solos give the

listener the time and space needed to relish and absorb the majesty of it all.

Just

as the show had begun with a Dylan/Motown one-two wallop, Garcia and his

cohorts chase “When I Paint My Masterpiece” with Stevie Wonder’s Motown

masterpiece, “I Was Made To Love Her.” Like “Expressway To Your Heart,”

Wonder’s genius is transformed into a colossal instrumental. The symmetry of

this concert is uncanny. One and one is two. Two and two is four.

On “Expressway,” the band latches onto a tight groove before Garcia comes off,

but on Wonder’s tune, Garcia’s en fuego

from the get-go. Graciously, Jerry defers to Merl, and the funky organ grinder

swamps the studio with R&B. Kahn and Kreutzmann crank the tempo, imploring

Garcia and Saunders to take it beyond their comfort zone. Like Ali in his

prime, Garcia’s creative flow is endless. There’s never a dull moment, aborted

lead, or hesitation of any kind.

Amazingly,

this was Garcia’s debut of “I Was Made to Love Her,” an instrumental he would

only perform six times, and never again after 1974. All of this experimentation

by Garcia was stunning considering what a groundbreaking year 1972 would be for

the Grateful Dead. After a short run of shows at Manhattan’s Academy of Music

in March, the Dead barnstormed Europe for six weeks, which led to the

idiosyncratic triple album, Europe ’72,

which once again showcased the mystical musings of Robert Hunter. On a

100-degree day in August, the Grateful Dead melted minds with a three-set spectacular

on Ken Kesey’s farm in Oregon. The band’s fall tour was even hotter; but all of

this was not enough for Garcia. He was driven to explore and pay homage to the

music he cherished. And this band he formed with Saunders and Kahn completed

Garcia as an artist. The music would never stop.

The

jam on 2-6-72 doesn’t need an exclamation point, but Garcia provides the

punctuation with Doc Pomus’ “Lonely Avenue.” Once again, the song symmetry is

there—a Stevie Wonder number is followed by a tune that his mentor, Ray

Charles, made famous. “Lonely Avenue” also pairs off well with the earlier

blues scorcher, “That’s All Right.” Here’s to the slipstreams of imagination

that flow through a gifted mind.

During

the melancholy intro, Garcia’s guitar weeps: “I could cry, I could cry, I could

cry…I could die, I could die, I could die. I live on a lonely avenue.” Tears

fill each syllable as Jerry belts out, “My room has got windows and the

sunshine never comes through.” And the way he achingly sings, “I live on a

Looonleyyyy Ave-ah-nue…” It’s pure heartache—the blues minus humor, irony, or

defiance. Garcia’s voice calls, and his guitar responds patiently to his own

pleas.

Garcia

lived on the same Lonely Avenue as Doc Pomus and Ray Charles. These musical

brothers are bonded by the pain of suffering through unspeakable childhood

tragedies. Jerry Felder, who later changed his name to Doc Pomus, was crippled

by polio at a young age. Ray Charles Robinson completely lost his eyesight when

he was seven, but prior to that, he witnessed the drowning of his brother

George in a laundry tub, a vision that would forever haunt him. When Garcia was

five, he may have witnessed the drowning death of his father Jose on a fishing

trip. It isn’t clear whether Jerry actually saw the drowning, or if it became a

learned memory from him hearing the story retold; but either way, the pain of

losing his father was unbearable. A year earlier, Jerry had two-thirds of the

middle finger on his right hand severed as he was steadying wood for his older

brother, Tiff. Yes, five-year-old Tiff was swinging the axe that accidentally

severed Jerry’s finger. Doc, Ray, and Jerry were all too familiar with growing

up on Lonely Avenue .

In

the heat of this Pacific High “Lonely Avenue,” Garcia bends his guitar strings

until they screech and scratch with all the surpassed pain of his childhood

during the solos, most notably, the second one. The sky’s a-crying as Garcia

methodically plots his attack and unloads it with the fervor of a preacher

prognosticating the apocalypse. Kahn’s a demon, thumping with all the madness

in his slender frame, prodding Garcia past the point of no return. Climaxing

with a mandolin-like tremolo, Garcia kicks on the wah-wah pedal to infuse some

final despair. Clearly Garcia is a learned disciple of the blues tradition.

This cathartic journey is bound to rattle your bones and shock your brain.

“How

Sweet It Is” wraps things up; but after “Lonely Avenue” it’s anticlimactic,

like watching a battle for bronze. In a rousing ninety-minute romp, Pacific

High radiates the talents of Garcia better than any studio release of the

Grateful Dead or Jerry Garcia Band. Beyond any shadow of doubt, 2-6-72 features

the finest renditions of “Expressway To Your Heart,” “That’s a Touch I Like,”

“Save Mother Earth,” “I Was Made to Love Her,” and “Lonely Avenue.” It’s a

rolling rhapsody of masterpieces in their early prime, raging in all their

glory.

In

one impromptu performance, Garcia and mates assembled and reinterpreted an

anthology of Americana that covered a vast spectrum of musical genres linking

legendary lyricists and performers: Dylan, Lennon, Wonder, Charles, Presley,

Pomus, Rodgers, Gaye, Saunders, Winchester, Holland-Dozier-Holland, Gamble and

Huff. Although Lennon hails from the foreign shores of Liverpool, “Imagine”

became an American lullaby, a melody of hope for a burned-out nation. If one

were to arrange the originals of these songs for an album, the sum would be the

embodiment of essential Americana, perhaps the beginning of a modern companion

for Harry Smith’s extraordinary Anthology of American Folk Music

(1952).

Pacific

High has gone on to become a consecrated recording for Garcia aficionados, and

because it has yet to be officially released, it maintains the alluring appeal

of a bootleg. With the plethora of officially released Jerry Garcia Band

concerts, I can’t fathom why 2-6-72 hasn’t met the same fate. Possibly some

bootlegs are too hot for public consumption; they’re destined to remain in the

Bootleg Zone, where only true fanatics can access, trade and obsess over them.

This

rambunctious Pacific High jam was a crossroads performance for Garcia who,

against his will, had been anointed as the inspirational guru of the

Haight-Ashbury scene, just as Dylan had been anointed as the voice of his

generation. Dylan’s radical break from the folk scene came when he donned a

black leather jacket, strapped on an electric guitar, and blasted away the

peaceful expectations of those at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival with a

performance that was as outrageous as it was courageous. He temporally riled up

a few folkies, but more significantly, he turned on and influenced a budding

generation of rockers, including the Beatles, The Byrds, Jimi Hendrix, and the

Grateful Dead.

Critics

and fans have always tried to stamp and label Dylan, but as a solo performer

with a lot of nerve, Dylan has remained elusive, dodging other’s expectations.

On the other hand, Garcia was always trapped by the expectations of his rabid

fan base and those in the extended Grateful Dead family who depended on him for

their own livelihoods. Garcia could never pull off a Dylan and completely

reinvent himself. It’s well known that Jerry didn’t have a confrontational bone

in his body. Captain Trips never desired the leadership role in the Grateful

Dead, but sometimes history just crowns its heroes.

As

the years rolled by, Garcia would be worshipped by millions. He could never

file for divorce from the Grateful Dead, or his hippie kingdom. To cope with

this burden, Jerry escaped into a ceaseless assortment of chemical cocktails;

but his true love was creating and performing. With Merl Saunders and John

Kahn, Garcia formed the nucleus of a band that would sustain him—a shelter from

the storm. He found a musical outlet outside of the Grateful Dead without

raising any eyebrows or alienating followers. In fact, Deadheads loved and

embraced his new band; it was a natural extension of his artistic vision. And

this performance in Pacific High Studios was a signpost to the future. The

Jerry Garcia Band was busy being born, and it would never fade away.