Excerpt from Dylan and the Grateful Dead: A Tale of Twisted Fate

Dylan’s run at the Beacon began on October 10, 1989. That night I was at Shea Stadium for a Rolling Stones concert in support of their new album, Steel Wheels. The Stones were also playing Shea Stadium on the 11th, but I picked the right night to be there. Eric Clapton joined the Stones for a mind-blowing blues assault on “Little Red Rooster.” It was a phenomenal show with an elaborate stage production. Steel Wheels was their most rocking album in a long time. Even though their set lists didn’t differ much, I could have gone to see this show five nights in a row.

The Oh Mercy songs debuted on the tour’s opening night at the Beacon Theatre

were “Everything Is Broken,” “Most of the Time,” and “What Good Am I?” This trio

was also performed the following two shows. These were strong shows that I enjoyed

very much, but my memory of them was obliterated by Dylan’s astonishing performance

on Friday the 13th. Dylan stormed the stage in a gold lame suit and pointy white

boots. My evening unfolded like a surreal dream as I watched the proceedings from

the front row of the balcony with my Woodstock friend, Blaise. We smiled all night

as we watched Dylan and his bird nest hairdo wiggle away below.

Dylan opened with the Empire Burlesque rocker “Seeing the Real

You At Last,” which segued into “What Good Am I?” Possibly influenced by his time

with the Dead, Dylan was segueing songs more than ever before. Dylan went to Infidels for his third song, “Man of Peace,”

and followed with his live debut of “Precious Memories” from Knocked out Loaded. Dylan infused the night

with a breathless pace as he stood and delivered his newer songs without regard

for what people may have wanted to hear. Aware of the city he loved, Dylan turned

the clock back to his Greenwich Village days with an acoustic set that began with

“Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright,” and one for his hero, the man who drew him to

New York. “Song to Woody” was a loving gesture, and it struck the right emotional

chord for those on hand.

“Everything Is Broken” filled the Beacon

with bawdy rock and roll again. There could be no mistaking Dylan was sentimental

on this final night at the Beacon as he followed with “I’ll Remember You.” The final

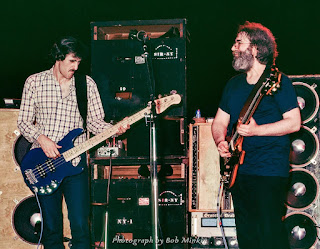

three electric songs came off like a communal exorcism. The stacks of speakers hanging

like worms in front of the Neo-Grecian décor were smoking from G. E.’s nasty blues

leads during “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.” Earlier Bob played

one for Woody, now he pivoted into one for Jesus, “In the Garden.” I hadn’t seen

this one since the Radio City shows. Dylan blitzed through “Like a Rolling Stone”

to end the set. It was hurried until he neared the finish line, and then the Transcendent

One lingered in the triumph of his consecrated anthem by tacking on a three-minute

harp solo before departing.

“Everything Is Broken” filled the Beacon

with bawdy rock and roll again. There could be no mistaking Dylan was sentimental

on this final night at the Beacon as he followed with “I’ll Remember You.” The final

three electric songs came off like a communal exorcism. The stacks of speakers hanging

like worms in front of the Neo-Grecian décor were smoking from G. E.’s nasty blues

leads during “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.” Earlier Bob played

one for Woody, now he pivoted into one for Jesus, “In the Garden.” I hadn’t seen

this one since the Radio City shows. Dylan blitzed through “Like a Rolling Stone”

to end the set. It was hurried until he neared the finish line, and then the Transcendent

One lingered in the triumph of his consecrated anthem by tacking on a three-minute

harp solo before departing.

The house lights stayed on as the band

continued to play, and I’m pretty sure that Dylan didn’t inform the band if he was

coming back. The jam stumbled to a confused ending and the crowd applauded, and

wondered if Bob would return. But there was not a word heard; goodbye, not even

a Shabbat shalom. Folklore states that the man in the gold lame suit hopped on a

bicycle and pedaled to his Manhattan apartment.