The “Shakedown Street” from Merriweather Post Pavilion

on 6-30-85 completely overshadowed the rest of the show. On the same date the year

before in Indianapolis, the Dead performed an epic “Shakedown” that was mortar

and brick in the construction of a killer show. June 30 offers us an eclectic

mix of Dead shows from different eras, as well as a legendary Jerry Garcia and

Merl Saunders show.

The “Shakedown Street” from Merriweather Post Pavilion

on 6-30-85 completely overshadowed the rest of the show. On the same date the year

before in Indianapolis, the Dead performed an epic “Shakedown” that was mortar

and brick in the construction of a killer show. June 30 offers us an eclectic

mix of Dead shows from different eras, as well as a legendary Jerry Garcia and

Merl Saunders show.

Situated in Columbia, Maryland, the

Merriweather Post Pavilion became Saratoga Springs South for Deadheads as the

band played Merriweather six times from ’83-85. The continuity of traveling

from Saratoga Springs to Columbia, or vice-a-versa, is an indelible communal

flashback for East Coast Heads of that generation. Except for the Derek and the

Dominos cover, “Keep on Growing,” and a lively “Big Railroad Blues,” there was

no reason to get excited about the opening set of 6-30-85.

Immortal performances sometimes take flight in

the tuning. When the band hits the stage for set two, you can hear nonsensical

words and sounds from the band as they’re tuning up. Garcia’s hypnotic tuning

is intoxicating ear candy—a countdown to ecstasy. The band slams the opening

chord as one. Thunderous reverberations shoot through the audience until the

musicians pound the next jarring chord. In

baseball, when a great hitter swings at a pitch and connects squarely sending

the ball into orbit, every fan (rooting for that team) in the stadium rises in

admiration knowing the ball is bound for homerun heaven before it gets there. After

two thunder chords, everyone in Merriweather was in motion, and experienced

Dead connoisseurs could instantly sense that this “Shakedown” was bound for

glory.

The tempo is perfect, and the funky groove is absolute.

Garcia flubs a word or two, but euphoria flows from his eager voice. Bobby and

Brent’s backing vocals rise to the occasion as the music fuses. Garcia breaks

into a between verse solo that burns and yearns against a grinding

groove—wonderful spacing, texture, and poignancy. The singing of the third

verse is improbably more compelling than the first two. As the “Nothing shaking

on Shakedown Street” chorus rolls o

As the

big jam evolves, the pavilion and surrounding fields are crammed with shuffling

feet, flailing arms, and pounding hearts. This goes on for several minutes, and

it’s wonderful for the part of the brain that controls bodily movement, but

it’s not all that mentally stimulating. That will change, because Garcia’s

playing possum—a few notes here and there turn into a decent run. The vacuum of

funky restraint opens the gates for a thrilling finale. Riding the band’s wave,

Jerry’s blistering runs unfold hotter and faster, and come together logically—an

advanced mathematical equation. Even the final chorus and instrumental walk off

is special. This may not be the hottest “Shakedown” ever, but it’s up there, an

indelible memory for those on hand. And it's probably the most popular “Shakedown”

of all-time.

“Shakedown” charges into a solid “Samson.” And

despite another “Cryptical Envelopments,” and a pretty “Stella Blue,” 6-30-85

never regains its footing after the brilliant opener. On 6-30-84, the Dead played

a standout “Shakedown” in the Sports and Music Center in Indianapolis, a killer

show start to finish

“Jack Straw” from Indianapolis starts the

impressive opening set. A lineup from Old Weird America follows: “Dire Wolf,”

“New Minglewood Blues,” and “Dupree’s Diamond Blues.” Jack Straw from Wichita cut his buddy down… Don't

murder me, I beg of you, don't murder me. Please, don't murder me… Well I'm a wanted man in Texas, busted jail

and I'm gone for good… Well

you know son you just can't figure. First thing you know you're gonna pull that

trigger…A touch of sloppiness

was overcome by extra effort as Garcia shredded extended solos in “Straw” and

Minglewood.”

Brent, Bobby, and Jerry follow with “Far from

Me,” “Brother Esau,” and “Ramble on Rose.” And then it’s was time for Weir’s

hypnotic masterpiece, Lost Sailor > Saint of Circumstance. The band’s giving

it their all. Phil pounds away as Jerry’s incursion leaves burn marks on the

way to the “Sure don’t what I’m going for” refrain. After one round Mr. Weir

hollers, “Just what the fuck you gonna do?” The momentum of the set could lead

to only one satisfying conclusion from Jerry, and that automatically ruled out

“Don’t Ease Me In” and “Might as Well.”

Since “Deal” was played as the first set

closer often, Jerry sometimes went through the words as if they were an

afterthought prior to the showcase jam. In Indy, Jerry sings as if he’s

rediscovering the joys of gambling and risk-taking. The jam flies high—a

massive collage of pulsating sound—relentless in its desire to please the most

discriminating Deadheads. There are many jammed-out versions from this era, and

the 6-30-84 “Deal” hangs in with the best

The Indianapolis “Shakedown” isn’t as dramatic

or as masterfully crafted as the one from Merriweather. It has an aggressive

pace that never backs off. Garcia pokes around on top of the steady groove.

There’s no trickery or intricate scheme—Jerry and the Boys are turned-up full

blast. After a substantial run, the band’s lost and can no longer return for

the “Just got a poke around” finale. Jerry suggests “Playin’.” As the band

collects themselves Weir sings, “Some folks trust to reason, others trust to

might. I don't trust to nothing. but I know it come out right.”

Off they go, bended strings unwind a cosmic

melody. There’s a foggy vibe as Jerry noodles around latching on to ideas and

letting them go. Around the eleven-minute mark the jam intensifies and has a

“Let it Grow” like feel. Eventually the band weaves into the familiar terrain

of “Terrapin Station.” The crowd’s ecstatic when Jerry’s weary voice croaks,

“Let my inspiration flow.” The epic anthem shines instrumentally as Jerry croons

as best as he can. This three-song pre-Drums segment is a snapshot of the

slightly sloppy yet attractive style of the Dead on a good night in ‘84.

Garcia’s en fuego for the Space > Playin’

reprise. Surprisingly, the band follows with a Weir combo, Truckin’ >

Spoonful, and Garcia answers with Stella Blue > Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’

Bad. The playing over the last stretch of the show is average, but overall, the

creative song selection, and improvisational surplus of this performance makes

6-30-84 one of the top-shelf shows of the year.

June 30 also features the Dead playing on

consecutive years in their prime. Their 6-30-74 Springfield Civic Center

performance commences with an unusual one-two punch, “Don’t Ease Me In” and

“Black Throated Wind.” It’s a fetching collection of tunes as they take a

summer stroll through Old Weird America; “Peggy O,” “Jack Straw,” “Loser,” and

then they dazzle the faithful with rock/folk/fusion: "Greatest Story Ever

Told,” and “Cumberland Blues.” The final

segment of the set is a distinctive improvisational combo that defies standard categorization

and can only be labeled as Grateful Dead music.

June 30 also features the Dead playing on

consecutive years in their prime. Their 6-30-74 Springfield Civic Center

performance commences with an unusual one-two punch, “Don’t Ease Me In” and

“Black Throated Wind.” It’s a fetching collection of tunes as they take a

summer stroll through Old Weird America; “Peggy O,” “Jack Straw,” “Loser,” and

then they dazzle the faithful with rock/folk/fusion: "Greatest Story Ever

Told,” and “Cumberland Blues.” The final

segment of the set is a distinctive improvisational combo that defies standard categorization

and can only be labeled as Grateful Dead music.

A colorful jam emerges out of “Playin’ in the

Band.” Unlike the psychedelic attack mode of versions from ’72 and ’73 (which I

love), the jam on 6-30-74 is an aural painting, a mellow mind-bender. They stretch

it out for fifteen minutes, and before redundancy creeps in, the band boldly strides

into “Uncle John’s Band.” “Playin’” is the ideal musical exercise for igniting

a hot “UJB.” The noodling of “Playin” seems to echo and influence the solos in

“UJB.” The crisp “UJB” instrumentals roam free. After a wonderfully harmonized

“Uncle John’s,” the band steams back to “Playin’” for a booming reprise.

The second set of 6-30-74 is not as

overwhelming as other shows from June ’74. The band could have been a little

tired, or maybe it was just artistic preference. A steady rolling “China Cat”

opens set two. It’s a pleasurable listen, yet it doesn’t have the intensity

factor of the fabulous “Cats” from 6-16-74 Des Moines and 6-26-74 Providence. The

big jam of the set was Truckin’ > Eyes of the World. The “Truckin’” jam

looks for an outlet and flirts with “Nobody’s Fault,” and hesitantly sputters

into “Eyes.” I’ve seen this version listed at twenty-four minute, but it’s

actually sixteen minutes of “Eyes;” the rest is unrelated space. There’s an

interesting segue in the set ending Not Fade Away > GDTRFB.

A year earlier, the Dead played the Universal

Ampitheatre, Los Angeles on 6-30-73. The opening set’s stocked with excellent

Jerry performances of “They Love Each Other,” “Birdsong,” and “Row Jimmy.” A captivating

“Black Peter” makes a surprise appearance before “Playin’ in the Band”

stretches the collective mind of the audience before break.

Set two is short, but the band delivers as

Keith twinkles electric piano during Dark Star > Eyes. Uncharacteristically,

“Eyes” is longer than “Dark Star” by three minutes. I’m fond of the soft-shoe

progression into “Eyes.” A typically hot ’73 rendition unravels, and around the

elven minute mark, the structure of the song loosens, and Keith chops away between

Jerry and Phil as Billy keeps the groove steady. It sounds like they may veer

from “Eyes,” but Phil emphatically reinstates the outro theme. This has a

rockabilly/jazz feel, and the length and loose jamming make the 6-30-73 “Eyes”

must listen material. Sweet “Stella Blue” is followed by a twangy romp through “Sugar

Magnolia.”

In a somber mood, the Dead rolled into

Portland International Speedway on 6-30-79. The day before, Little Feat’s

Lowell George died of a heart attack from an accidental cocaine overdose. George

was producer for the Dead’s most recent record, Shakedown Street. After a short, well-played opening set, the Dead

launched set two with a I Need a Miracle > Bertha > Good Lovin’ combo.

The first and last songs formed a Shakedown

Street sandwich. Garcia’s solo out of “Miracle” was substantial. Jerry

seemed to lose interest in extending the “Miracle” solo down the line. The

other notable segment from this show was Estimated > He’s Gone. It was a

cathartic performance with the passing of Lowell.

The Dead played on June 30 every year from

1984-1988. I’ve already discussed the first two years, and there’s not that

much meat from the other shows. It’s worth noting two performances from Silver

Stadium, Rochester on 6-30-88. Before busting into China Cat > Rider, the Dead

riff on their only version of the iconic instrumental “Green Onions,” for a few

minutes. After Cat > Rider, Rochester catches the second performance of the

new Garcia/ Hunter tune, “Believe It or Not.” Jerry delivers a fine vocal of

this tune which was only played seven times and not included on Built to Last.

There wasn’t much joy on the Dead’s last tour

as an assortment of hassles and tragedies seemed to unfold nightly. Their show

in Pittsburg’s Three Rivers Stadium on 6-30-95 was an exception. The band and

their devotees enjoyed a magical second set. As the band harmonized the opening

of the Beatles “Rain,” a steady downpour soaked the delighted audience. I love

the Dead arrangement and it’s evident that Jerry’s digging it. “Rain” is one of

their premier later-day covers.

“Rain” is followed by “Box of Rain,” “Samba

(in the rain),” and “Looks Like Rain.” The first two songs are the best of this

soggy segment. The ensuring “Terrapin Station” is a little sluggish, and after

Drums Jerry delivers a poignant “Standing on the Moon.” To certify the show as

memorable, there’s a rare “Gloria” encore. Many observers could sense the end

was near for Garcia, but on 6-30-95 there was still joy in Deadville.

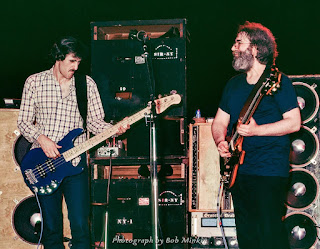

There was boundless optimism in the air on

June 30, 1972 when Jerry Garcia took the stage in the Keystone Korner with Merl

Saunders, John Kahn, Bill Vitt, and Tom Fogerty. The Dead had recently returned

from their legendary tour of Europe. Before resuming touring with the Dead in

July, Jerry was playing intimate venues on the West Coast with this group.

Earlier in the year, Garcia played a date with Saunders, Kahn, and Kreutzmann

at Pacific High Studio on 2-6-72, that I rank as the greatest Jerry Garcia

show. In relative anonymity, Garcia was creating some of his finest music, and

having a ton of fun in the process.

Garcia and mates kick off 6-30-72 with the

blues infused rush of “It’s No Use,” and follow with the R&B hit

“Expressway to Your Heart,” which was written by the prolific songwriting team

of Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. “Expressway” was released on Merl Saunders’

album Fire Up. The infectious groove

of the instrumental captures the essence of the early Garcia/ Saunders sound.

The Keystone Korner jam starts off tight and then dissolves and reorganizes

again as Garcia unleashes a tornado of sound. This is a compelling soulsville

exploration, probably the second best “Expressway.” Check out the 2-6-72

“Expressway” to hear one of the extraordinary instrumentals of Jerry’s career.

The Grateful Dead covered “One Kind Favor” in

their early days, and Garcia mastered it on the third number of 6-30-72. As

“One Kind Favor” takes shape, Garcia, Saunders, Kahn, Fogerty, and Vitt (sounds

like a law firm, doesn’t it?) slither into a Southern/ Garcia groove— “House of

the Rising Sun” meets “Mississippi Half-Step Uptown Toodeloo” on the California

coast. Jerry’s pipes unleash shrill howls that beg, plead, and scream for

salvation. Prior to the chorus, Kahn thumps his bass like he’s nailing a coffin

shut with a power drill. The music’s haunted with goblins, ghosts, and graves.

Garcia’s guitar’s a-stinging—Cajun voodoo blues fortified by the demons that

Saunders drains from his Hammond organ.

Garcia continues to cultivate a Southern

ambiance with an atmospheric performance of Jesse Winchester’s “Biloxi.” Next

is a torrid “That’s All Right Mama,” and that’s followed by another song that

would go on to become a Garcia Band staple, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie

Down.” This is paced somewhere in between The Band’s brisk version, and the

dawdling JGB versions to come. Garcia and Saunders in a short period of time

had put together a diverse collage of American music performed with passion and

soul.

Over the years, Garcia would explore Bob

Dylan’s oeuvre, and expand upon his songs with more enthusiasm than any other

renowned artist. With all the new compositions and musical groundbreaking that

the Dead were involved in at the time, Garcia still had an insatiable appetite

for more. In Keystone Korner, Garcia performs a definitive “It Takes a Lot to

Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.” Jerry’s euphoric vocal phrasing is filled with

visceral outbursts and flourishes. The band locks into a deliberate groove like

on the Highway 61 Revisited track.

Garcia dives into three yearning blues solos, each one’s more intense and

committed than the one that preceded it. Jerry masters all aspects of Dylan’s

creation: the ambiance, rhythm, and spacing of the song. Jerry’s searing blues

solos channel the spirit of Michael Bloomfield’s contributions on various

outtakes from the Highway 61 Revisited

sessions.

Garcia and friends are attentive and patient

as they jam ample versions of “After Midnight” and “Money Honey.” The musicians

wind-down this memorable evening and add to this glorious collection of songs

with a marathon run through “Are You Lonely for Me” a number one R&B hit

for Freddie Scott. The first instrumental sets the tone—a lost and lonely

journey that will resolve itself on Jerry’s timetable. At the end of the second

and final verse, Garcia howls, “I’m lonely baby, lonely and blue. I’m lonely

baby, I’m a-lonely for you. Ah girl…Yes I am!”

The heavens have opened. Here come the blues,

pouring down like hail. Garcia’s men are coming through in waves, communicating

in a unified, hypnotic trance. Garcia’s improvising on a mound of sound, a

skier riding the course, fantastically in and out of control. At times it’s an

amazing spectacle; there should be 100,000 people swaying and waving banners as

they watch a closed-circuit broadcast of this in a soccer stadium. At times

it’s long-winded, but Garcia forges ahead. Take

what you need and leave the rest. One wave of blues follows a funky groove,

and then another wave of blues washes over that. Garcia breaks it down over and

over again until “Are You Lonely for Me” crackles into freeform improvisation,

Ornette Coleman territory. The improv seems like it’s running out of steam as

the tape ends, but unsubstantiated reports claim that Garcia jammed for another

hour and brought a guest guitarist on stage. It’s certainly plausible. Anything

and everything was possible for Jerry in 1972.