Excerpt from Grateful Dead 1977: The Rise of Terrapin Nation

After their Toronto adventure, the Dead breezed into the middle

of New York State and landed in Hamilton, one of the friendliest towns in America

according to Forbes Magazine. Hamilton,

which is 104 miles west of Albany, is home to one of the premier liberal arts schools

in the country, Colgate University. The similarities between Colgate and Cornell

were striking. A memorable evening was blowing in the wind on 11-4-77, which happened

to be my fourteenth birthday. I had just discovered Led Zeppelin, and the Grateful

Dead was a complete mystery to me. Although, any Deadhead takes great pride in a

legendary show on their birthday, whether they were there or not.

The Colgate affair begins with “Bertha” fireworks—sly, rapid-fire

guitar phrasing. Garcia’s full of creative impulse as he later sparks “Brown-Eyed

Women” with similar phrasing. Some nights Garcia finds a groove, or certain style

of playing, a motif that’s unique to that show and that show only. Garcia’s fingers

are flying in Colgate. Just when you think he’s finished a passage, he sneaks in

a quick run. Jerry also treats us to some wonderful vocal embellishments during

“Dupree’s Diamond Blues.”

Some of the finest group efforts since May are featured on

11-4-77. The set-ending “Let it Grow” is phenomenal, right up there with the one

from DeKalb five nights earlier. After Weir bellows, “Rise and fall,” Keith steps

up to lead the instrumental. The sonic landscape is elegant and jazzy as Garcia

smoothly connects the dots in a vacuum of high-velocity picking and strumming. Weir,

Lesh, and the rhythm devils shift gears precisely, and Garcia and Godchaux have

all the answers. This jam doesn’t explode like DeKalb. It’s an improbably fluid

display of elaborate improvisation. And the outro jam is the longest of any ‘77

version—The Boys are hot, and Jerry noodles on until “Let It Grow” recedes into

its final signature line.

Was 1977 the end or beginning of an era for the Grateful Dead,

or both? They were moving towards the future with an arsenal of originals that would

define them, but they were peaking as band, they would never consistently sound

this awesome again, and they would never have this much fun again, with each other,

and the audience. When they take the stage for act two, Lesh introduces his mates

as the Jones Gang. MC Phil saves his best roast for Weir, “In center stage, ladies

and gentleman, a star whose name has gone behind him, even on to the farthest galaxies

(diabolical laughter), Bob Jones!”

“Samson and Delilah” roars out of the gates. Pumped by his

fabulous intro, Weir’s vocals are ferocious, and the band causes quite a racket.

Following the final “Tear this old building down,” Garcia’s guitar saws its way

into the first “Cold Rain and Snow” of the

year. A traditional folk number that appears on the debut Grateful Dead album of 1967, “Cold Rain and Snow” is one of those tunes

with the Dead’s trademark magnetic groove. You can hear the excitement of the moment

in Jerry’s voice, and the band’s demonstrative playing as they try to channel the

energy into the soothing aura of the song. Many a ‘77 second set could have benefitted

greatly from a sprinkling of “Cold Rain and Snow.”

The weirdness begins in Cotterell Gym with a “Playin’ in the

Band” stomp. The roulette wheel spins—where and when she will stop, nobody knows.

Deep inside the beast, Weir introduces some “Eyes of the World” chords and Garcia

peels off some “Eyes” licks, but it sounds like this thing will swing into “Uncle

John’s Band.” But the “Eyes” seed has been sown, and Garcia latches onto it. Yes!

They’re storming into “Eyes.” This is the type of ingenuity that has been lacking

through most of October.

“Eyes” whips ahead at a terrific tempo as an amused Garcia

riffs this way and that way before breaking into piercing leads. Weir strikes up

some interesting-sounding chord progressions that aren’t synching with what Garcia’s

doing, but the clash of rhythm and pitch sounds brilliant and gives this “Eyes”

a unique tension. Garcia unravels a tasty intro before things settle into a hyped

groove. Any instant now, Garcia’s going to sing the opening verse, but it appears

he’s transfixed by the rolling rhythm, so he decides to reel off another cascading

solo, and eventually he ducks back into the chord motif. The delirious crowd roars

approval that can clearly be heard on the soundboard tapes. After Donna, Bobby,

and Jerry harmonize the opening chorus, the band storms ahead—a shuffling staccato

beat. This is loony tunes, Wile E. Coyote is chasing the Road Runner. Garcia’s solos

are aggressive, and there’s no indecision as he channels the muse that only he has

access to. At the end of the first solo, Garcia introduces the repetitive taunting

licks that I so admire. For the most part I prefer an “Eyes” with a slower tempo,

but this is an extraordinary display, a standout in a year of excellence.

Garcia’s still breathing fire as “Eyes” finds its way to “Estimated

Prophet” through the back door. Every once in a while you have to shake things up

by reversing the natural order. The melancholy wah-wah wailing of the post-verse

“Estimated” jam works its way into a wicked, wicked, “The Other One.” Phil bombs

as Jerry shreds, and each lap is more intense. There’s no putting on airs or teasing,

just primal Grateful Dead. This is a freaking hand grenade. The sonic spirals tighten

with each pass, the heat of their psychedelic past intertwines with their powerful

professionalism—1969 comes face-to-face with 1977. The spectacular jam culminates

with the opening verse, “Spanish lady come to me she lays on me this rose.” A drum

solo follows. Everything you ever need to hear in “The Other One” occurs in one

jam with one verse. Scintillating.

“Iko Iko” materializes out of drums. It’s the most complete

and best rendition of the year, and by the ‘80s, it will blossom into one of the

band’s beloved tunes. The segue into “Stella Blue” flows like a river to the sea,

and Garcia frames the magic with a unique opening “Stella” solo. Jerry has to get

in his introspective ballad, and this fits the bill. Garcia moans a final “Stella

Blue-uwhew” and scurries off into a high-frequency solo that eventually dips back

into “Playin’ in the Band.” This is such a fulfilling loop that you can forget how

it all began. The “Playin’” space is sparse, but the jam after they reprise the

last verse is insane; everybody in the gym is rocked and rolled to the cores of

their souls. “Johnny B. Goode” bids goodnight to Hamilton, New York.

It must have been an amazing two-hour ride for the musicians,

and those wise enough to be following them to the next gig at the War Memorial Auditorium

in Rochester, a Grateful Dead stronghold. Between 1973 and 1985, this auditorium

hosted ten Dead shows. Sitting near the southern shore of Lake Ontario, Rochester

is the third-largest city in New York State, and there are many fine institutions

of higher learning in the area, which equals more Deadhead conversions. Between

1982 and 1985 I witnessed five smoking Dead shows in the War Memorial. I can’t explain

the appeal of seeing the Dead in Rochester, but I’m glad I was there. There was

raw energy in that building—Rochester sparked the Dead and the Dead breathed life

into Rochester. Those who were there on 11-5-77 were treated to a memorable show,

although it wasn’t as brilliant, start to finish, as Colgate was.

When the Grateful Dead take the stage in Rochester, the crowd

surges to greet them, and Weir promptly asks them to take a step back before the

band busts into “New Minglewood Blues.” Real pandemonium kicks in when the crowd

hears “Mississippi Half Step,” the first one of the tour. You can tell the band’s

pumped, the vocals and between-verse solos are crisp. The pre-“Rio Grande” jam is

an escalating stream of jubilation—pure aural gratification that’s reminiscent of

the Boston Garden “Half Step” on 5-7-77. Phil’s bass registers readings on the Richter

scale. This is a tidal wave of sound—the band surfs with Garcia as he improbably

finds creative paths to extend the momentum and forward movement of the jam without

changing course. When the wave crashes and all that’s left is the pretty whisper

of the “Rio Grande” melody, the audience rejoices. The final instrumental is shorter,

but it’s cut from the same cloth as the previous one. To borrow a ‘77 Weir catchphrase,

“Ladies and gentleman, I think we have ourselves a winner. Everything is just exactly

perfect.”

When the Grateful Dead take the stage in Rochester, the crowd

surges to greet them, and Weir promptly asks them to take a step back before the

band busts into “New Minglewood Blues.” Real pandemonium kicks in when the crowd

hears “Mississippi Half Step,” the first one of the tour. You can tell the band’s

pumped, the vocals and between-verse solos are crisp. The pre-“Rio Grande” jam is

an escalating stream of jubilation—pure aural gratification that’s reminiscent of

the Boston Garden “Half Step” on 5-7-77. Phil’s bass registers readings on the Richter

scale. This is a tidal wave of sound—the band surfs with Garcia as he improbably

finds creative paths to extend the momentum and forward movement of the jam without

changing course. When the wave crashes and all that’s left is the pretty whisper

of the “Rio Grande” melody, the audience rejoices. The final instrumental is shorter,

but it’s cut from the same cloth as the previous one. To borrow a ‘77 Weir catchphrase,

“Ladies and gentleman, I think we have ourselves a winner. Everything is just exactly

perfect.”

“Looks Like Rain” is a soothing selection in the aftermath

of “Half Step,” although the crowd’s still surging towards the stage, prompting

another short rendition of “Take a Step Back.” A concerned Garcia makes this dire

proclamation:

“The people up front are getting smashed horribly again. If

everybody on the floor can sort of try to move back, that would be helpful. It’s

hard for us to get off seeing smashed human bodies up here. You know what I mean?

Give us a little mercy.”

A perky “Dire Wolf” takes flight, and pretty soon everybody

in the War Memorial is singing, “Don’t murder me. I beg of you don’t murder me.

Plea—ease, don’t murder me.” Surging crowds and rowdy group behavior were nothing

unusual back in 1977, whether you were at a Grateful Dead concert, a night club,

or a baseball game. After nine people were trampled to death trying to get into

a Who concert in Cincinnati in 1979, things slowly changed. Out-of-control mobs

became frowned upon.

Mama Tried > Big River follows. This pairing of electrified

Merle Haggard and Johnny Cash did little to settle down the hyped crowd. A stinging

solo with a nasty bite concludes “Big River.” Jerry belts out a soulful “Candyman”

that’s followed by “Jack Straw.” It’s great to hear “Straw” anytime, but it always

seems to be at its best late in the set, and this smoking version validates that

claim. The set closes with a “Deal” that’s as provocative as can be. Down the road,

Garcia added a solo to “Deal” that made it a tour de force set closer.

Set two starts with fiddle-faddle from Phil that winds into

a slow march, and an unprecedented third plea to take a step back. Phil takes the

honor of leading his mates into a leisurely paced “Eyes of the World.” Who is this

band? Last night’s “Eyes of the World” was a speeding bullet, as was this opening

set. It’s a welcome change of pace, and that’s what makes the Grateful Dead the

best at what they do, because they’re the only ones who do what they do. My apologies

to Bill Graham for mangling his iconic characterization of the band.

Set two starts with fiddle-faddle from Phil that winds into

a slow march, and an unprecedented third plea to take a step back. Phil takes the

honor of leading his mates into a leisurely paced “Eyes of the World.” Who is this

band? Last night’s “Eyes of the World” was a speeding bullet, as was this opening

set. It’s a welcome change of pace, and that’s what makes the Grateful Dead the

best at what they do, because they’re the only ones who do what they do. My apologies

to Bill Graham for mangling his iconic characterization of the band.

A fine “Eyes” bolts into “Samson and Delilah.” However, there’s

no reason to get excited. Garcia’s determined to keep things mellow. His ensuing

selections are “It Must Have Been the Roses,” “He’s Gone,” and “Black Peter.” The

jamming highlights of this set occur during Weir tunes. There’s a sparkling climax

to the second solo of “The Other One,” and the entire band goes bonkers during a

vivacious serving of “Sugar Magnolia.”

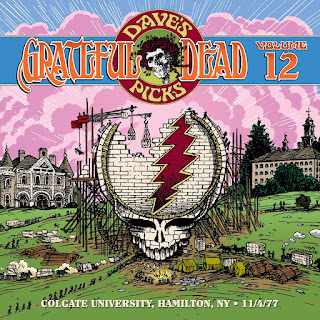

The 11-4-77 Colgate show was released as Volume 12 in the

Dave’s Picks series in 2014. And 11-5-77 Rochester was released as Volume 34 in

the Dick’s Pick’s series in 2005. No series has yet to claim the finale of this

three-set run in Binghamton’s Broom County Arena, a show revered by many Dead aficionados.

A two-and-a-half-hour car ride southeast of Rochester, Binghamton is situated near

the border of Pennsylvania. The two biggest institutions in town were IBM, and the

State University of New York at Binghamton. No matter how far these college towns

were from New York City, the enthusiasm of these adoring collegiate crowds turned

the Grateful Dead on as if they were playing a friendly facsimile of Madison Square

Garden.

Amidst a thunderous ovation and a thick cloud of marijuana

smoke, the ceremony begins with “Mississippi Half Step.” After such a phenomenal

performance the night before, the band can’t resist the temptation of playing it

again. As the Dead rolled into the ‘80s, it was pretty much an unofficial rule that

songs were never repeated at successive shows. Throughout their career they always

mixed up set lists and made shows as distinctive as possible with their improvisation,

but soon they would take that concept to another level. Although, I can’t imagine

that anyone in Binghamton was bummed because they had played “Half Step” the night

before, or that anyone in Rochester was stressed over the fact that “Eyes of the

World” and “The Other One” had been played the night before in Colgate.

Guess what? New York hipsters received another brilliant “Half

Step.” It’s hell to rank these things, but this is what I choose to do. I’ll give

the Rochester “Half Step” the nod over Binghamton by a split-hair decision. The

Binghamton jams have fierce, high-pitched fanning crescendos from Garcia. The Rochester

version is a cascading scale thriller without any superfluous fanning. If you have

no idea what I’m talking about, listen to these gems and compare them. Whatever

you conclude, you will be better off for performing this exercise.

“Jack Straw” follows in the footsteps of “Half Step.” The

essence of the song comes to life—the rhythmic flow is breathtaking, and the group

harmonizes with a soulful feeling. Bobby hollers, “You keep us on the run,” and

the fuse is lit, a cannonball of sound is fired with signature Binghamton high-pitch

fanning to close out the affair. Those crazy New York kids have to be warned again

about rushing the stage. The heat of the moment is captured in a tipsy “Tennessee

Jed.” There’s extra fire in Garcia’s singing and the guitar licks that accentuate

Hunter’s lyrics. Garcia winds the solo up, stutter-steps his way to the peak, and

hits all the notes that make you want to yodel and yell, “Yeee-hahh!”

Mexicali Blues > Me and My Uncle is absurdly exciting.

For years to come, Me and My Uncle > Mexicali Blues would be a less than thrilling

staple of the live rotation. I think they got it right in Binghamton. This outlaw

partnership sounds better in reverse. A plaintive “Friend of the Devil” is next.

After six songs, 11-6-77 has traveled all across Weird America…Mississippi, southern

sky, Rio Grande, Texas, Detroit Lightning, Santa Fe, Great Northern, Cheyenne, Tulsa,

Wichita, Tucson, Bakersfield, South Colorado, West Texas, Santa Fe (again), Denver,

Reno, Utah, Chino, Cherokee. By adding the tales of “New Minglewood Blues,” “Dupree’s

Diamond Blues,” “Passenger,” and “Dire Wolf,” you have the makings of a soundtrack

for a classic Western movie. “The Music Never Stopped” rockets the set to a screaming

conclusion. The build-up jam is unreal here, and then all speed limits are exceeded

as the band batters Binghamton into a state of sweaty elation.

Mexicali Blues > Me and My Uncle is absurdly exciting.

For years to come, Me and My Uncle > Mexicali Blues would be a less than thrilling

staple of the live rotation. I think they got it right in Binghamton. This outlaw

partnership sounds better in reverse. A plaintive “Friend of the Devil” is next.

After six songs, 11-6-77 has traveled all across Weird America…Mississippi, southern

sky, Rio Grande, Texas, Detroit Lightning, Santa Fe, Great Northern, Cheyenne, Tulsa,

Wichita, Tucson, Bakersfield, South Colorado, West Texas, Santa Fe (again), Denver,

Reno, Utah, Chino, Cherokee. By adding the tales of “New Minglewood Blues,” “Dupree’s

Diamond Blues,” “Passenger,” and “Dire Wolf,” you have the makings of a soundtrack

for a classic Western movie. “The Music Never Stopped” rockets the set to a screaming

conclusion. The build-up jam is unreal here, and then all speed limits are exceeded

as the band batters Binghamton into a state of sweaty elation.

An audience recording of the first set of 11-6-77 was amongst

my first dozen bootlegs. The audience contributions complement the fiery music.

For every noteworthy highlight, someone let out a heartfelt yodel or yelp that accented

the moment. This audience tape is a prime example of how the fans were, to some

extent, musical collaborators inspiring the Grateful Dead. Many years later when

I got the soundboards of this show, it took me a while to assimilate to the pristine

sound minus the audience energy. These soundboards were also my first exposure to

the second set of 11-6-77. I wasn’t overly impressed with the second set, although

I hadn’t listened to it all that much. As I revisited tour ‘77 for this book, I

eagerly anticipated hearing part two of Binghamton again.

On Sunday night, Weir ignites the second set with a biblical

favorite, “Samson and Delilah,” and then Donna sings her spiritual number, “Sunrise.”

There’s a conscious attempt to slow down the tempo of “Scarlet Begonias.” Everything

sounds fine until Jerry forgets a verse, but redeems himself with a searing solo.

The music is sparse and trippy as the Scarlet > Fire terrain is navigated. It

sounds as if the ghosts of Cornell past have entered the Broome County Arena. The

sound of Garcia’s guitar has a dreamy glow as “Scarlet” spins forward. Yet there’s

no magic in the transition. Cornell is immortal for a reason. Garcia makes this

a memorable “Fire on the Mountain” thanks to a blistering between-verse solo.

A standalone “Good Lovin’” builds a bridge to the big jam,

which commences with “St. Stephen.” A smooth run through this revered tune morphs

into a jam that gets spacey before segueing into drums. If this were May, I would

be thrilled with these developments; but after hearing the jams of the uninterrupted

“Stephens” from SMU, DeKalb, and Toronto, this is a little disappointing. Post drums

begins with a concise Not Fade Away > Wharf Rat > St. Stephen Reprise, which

rolls into the surprise highlight of the set, “Truckin’.”

The post “Truckin’” jam spirals to its usual crescendo and

mysteriously dissolves. The music slowly rises and the band stops, and then they

only play in short bursts to accentuate Garcia’s soloing, which takes on a Jimmy

Page-like tone. It’s a very cool and abnormal Grateful Dead moment. Pretty soon,

Lesh and the drummers are hammering away as the “Truckin’” monster revs up for one

last thrashing—an amalgamation of blues, acid rock, and heavy metal to end the last

East Coast set of ‘77. A “Johnny B. Goode” encore is the only choice that makes

sense at this point. Surprisingly, “Terrapin Station” wasn’t played at any of the

last three shows.

The post “Truckin’” jam spirals to its usual crescendo and

mysteriously dissolves. The music slowly rises and the band stops, and then they

only play in short bursts to accentuate Garcia’s soloing, which takes on a Jimmy

Page-like tone. It’s a very cool and abnormal Grateful Dead moment. Pretty soon,

Lesh and the drummers are hammering away as the “Truckin’” monster revs up for one

last thrashing—an amalgamation of blues, acid rock, and heavy metal to end the last

East Coast set of ‘77. A “Johnny B. Goode” encore is the only choice that makes

sense at this point. Surprisingly, “Terrapin Station” wasn’t played at any of the

last three shows.

Colgate, Rochester, and Binghamton are up there with any successive

three-night stand the Dead put on. They left behind a trail of inspiration for those

who were there, and those who would listen to the tapes in the future. Friends told

friends, students told students, and the Grateful Dead continued to play on college

campuses year after year, especially in their favorite breeding ground, New York.

They played in Syracuse, Utica, Niagara Falls, Buffalo, Ithaca, Glens Falls, Troy,

Albany, Saratoga Springs, Lake Placid, Rochester, and Binghamton. Although some

of these venues weren’t on campuses, they were in centrally located areas where

the collegiate Deadheads could converge. The Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia Band

were inspiring a new generation of Deadheads, a flock of devotees more rabid than

their predecessors. Terrapin Nation was on the rise, and central New York was a

fanatical hub.

GRATEFUL DEAD 1977: THE RISE OF TERRAPIN NATION

GRATEFUL DEAD 1977: THE RISE OF TERRAPIN NATION