“Scarlet Begonias” was born in the

thick of the first set on March 23, 1974, in the Cow Palace, located in Daly

City, on the border of San Francisco. Garcia’s feeling the lyrics and the

sublime musical arrangement. The unhinged enthusiasm in Jerry’s voice is

palpable as he growls, “I knew without asking she was into the blue-whose…I ain’t

often right but I’ve never been wrong! It seldom turns out the way it does in

the song. Once in a while you get shown the light in the strangest of places if

you look at it right.” “Begonias” differed from the outlaw/drifter milieu that

dominated Hunter/Garcia songs in the early ’70s. Hunter and Jerry were now

writing songs that were unique to the Grateful Dead experience—flexible

compositions with danceable grooves and room for improvisation built within.

Later in the year, “Scarlet Begonias” would appear on Mars Hotel, and as they played the song throughout ’74, the outro solo blossomed into an aural sensation.

There’s no delight quite like a standalone “Scarlet.”

A few tunes after the birth of

“Begonias,” the Dead introduced a Weir/Barlow song, “Cassidy,” which pays

homage to Barlow’s newborn daughter, Cassidy Law, and Neal Cassady, the revered

Merry Prankster. Donna sings along with Bob as the song cautiously takes flight

and abruptly ends in just over three minutes. “Cassidy” steadily became a

better live song year after year. By the early ’80s, it became one of the band’s

most anticipated first set numbers. After the rocky debut, the Dead unloaded on

the always reliable and wonderfully expansive “China Cat” jam—an iconic ’74

treat.

Set two began with the final Playin’

> Uncle John’s > Morning Dew > Uncle John’s > Playin’ ensemble.

This was the third performance of this loop de jour, which was born in the

Winterland on 11-10-73. A week later the Dead visited Pauley Pavilion, where

Deadhead Bill Walton and the UCLA Bruins were dominating the world of college

basketball. In the house where coach John Wooden preached to his players about

the benefits of enthusiasm, alertness, initiative, ambition. adaptability, and

team spirit, the Grateful Dead exhibited all of those qualities, as if Wooden

gave them a pep talk prior to the definitive performance of Playin’ > UJB

> Dew > UJB > Playin’ on 11-17-73. The final version in Cow Palace was

spectacular at times, but it didn’t have the effortless magnificence of

11-17-73. If I have one critical observation of the Cow Palace loop de jour,

it’s that the final “Morning Dew” solo isn’t as satisfying as when the Dead

finish it off with a momentous climax and Garcia’s final, “I guess it doesn’t

matter anyway.”

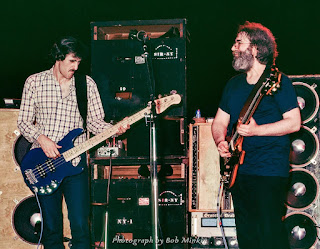

The other major unveiling in Cow

Palace on 3-23-74 was the Wall of Sound, a state-of-the-art sound system that

was as ambitious as it was cumbersome. The distortion-free concert gear, which

allowed the band to monitor their own sound, was the brainchild of Owsley

“Bear” Stanley. In addition to the benefits to the musicians, those who saw the

Grateful Dead in 1974 had a dynamic audio experience, unlike anything else

available to concertgoers at the time. The major downfall of the Wall of Sound

was the cost and the manpower needed to drag this monstrosity from city to

city. It was impossible for the band to continue touring with such a system, and

when the Dead hit the road again in 1976, the sound system was simplified.

The other major unveiling in Cow

Palace on 3-23-74 was the Wall of Sound, a state-of-the-art sound system that

was as ambitious as it was cumbersome. The distortion-free concert gear, which

allowed the band to monitor their own sound, was the brainchild of Owsley

“Bear” Stanley. In addition to the benefits to the musicians, those who saw the

Grateful Dead in 1974 had a dynamic audio experience, unlike anything else

available to concertgoers at the time. The major downfall of the Wall of Sound

was the cost and the manpower needed to drag this monstrosity from city to

city. It was impossible for the band to continue touring with such a system, and

when the Dead hit the road again in 1976, the sound system was simplified.

The Grateful Dead temporarily

retired from touring after their Winterland show on 10-20-74, but they returned

to perform four individual shows the following year, the first coming on March

23, 1975, in Kezar Stadium in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Since the Dead

were “retired,” the band was billed as Jerry Garcia and Friends for this

appearance at the SNACK Benefit Concert. Mickey Hart was a member of the band

again, and Merl Saunders joined the jam on keyboards. Also performing for this

Bill Graham benefit to raise money for San Francisco students who had arts,

sports, and culture funding cut from their school budget were the Doobie

Brothers, Jefferson Starship, Joan Baez, Santana, and Neil Young. There was a

surprise appearance as Bob Dylan and The Band joined Neil Young during his set.

Adding to the surreal atmosphere, a few days before the benefit, it was

discovered that there had been an accounting mistake, and the extracurricular

school activities weren’t going to be cut. The proceeds of the benefit were

donated elsewhere.

SNACKS was broadcast on FM radio,

and if one turned the show on while the Dead were playing, they might have

thought they were listening to the fusion jazz of Weather Report. The

thirty-two-minute instrumental segment begins with “Blues for Allah,” the title

track of the album that they were in the process of recording. All the lyrics

and arrangements for the album were created organically by the songwriters and

the band in the studio. In Kezar Stadium, the repetitive opening chord sequence

has an Arabian feel to it, ancient in nature. The segment they played this

night would have set the perfect ambiance when they were playing in front of

the Great Pyramids of Egypt in 1978.

Before they broke into “Stronger

Than Dirt or Milking the Turkey,” Merl and Keith traded keyboard licks as if

they were on stage with Miles. “Milking the Turkey” is split by a drums solo.

The group smokes throughout. They could have taken this acid jazz act with two

drummers and two keyboardists on the road for a tour. Their innovative debut

spins to a logical conclusion with a segue back to “Blues for Allah.” Garcia

slices and dices with supreme confidence. The band finally uses the microphones

to harmonize the melody line as “Blues for Allah” touches down. The strange new

material was met with an enthusiastic response from the audience, and a “Johnny

B. Goode” encore finished off this unique performance.

Prior to embarking on their Europe

’72 adventure, the Dead played a seven-night residency in the Academy of Music.

These were the last shows the band played in New York City until they played

the Beacon Theatre in ’76. The third Academy show on March 23 may be the best

of the Academy run. Psychedelic exhilaration fills the air as the Dead opens

3-23-72 with a surprise China Cat > Rider. Of the sixty-five versions of

this combo played over 1972, this was the only time it was an opener. They went

on to play an eighteen-song first set, a feat that was topped when they performed

nineteen tunes during the opening set of the last Europe ’72 show in London’s

Strand Lyceum.

Halfway

through the opening set, there’s a fluid rendition of Hank Williams’ “You Win

Again.” Garcia effortlessly channels blues and country in his hypnotic San

Francisco style—silky smooth singing with a piercing yet melodic guitar solo.

Jerry had that uncanny ability to take an iconic tune and reinvent it in the

spirit of the composer, thereby further shining a light on the magnificence of

the original. “You Win Again” debuted in late 1971 and was performed for the

last time on 9-28-72. With the influx of originals squeezing their way into the

Dead’s touring repertoire, a few covers had to be dropped, but “You Win Again”

always benefited any set it was in.

If you find that twenty or thirty

minutes of noodling in “Playin’ in the Band” is too much, then you’ll love the

tight, ten-minute “Playin” that anchors the Academy’s final segment of the

opening set. “Comes a Time,” “Bobby Mc Gee,” and “Casey Jones” close out the

marathon set in triumphant fashion.

A

ripping “Truckin’” from the recently released American Beauty thrills the crowd after intermission. Following a

lively “Ramble on Rose,” Pigpen delivers his new composition, “The Stranger

(Two Souls in Communion).” It’s a poignant and beautiful yet haunting blues

number that leaves us wondering what Pigpen was capable of if he had lived

another twenty years. This version is good, but not as developed as the ones

from Europe, where the band harmonizes with him. Pigpen had a busy night on

3-23-72, singing five tunes. Later in the set, there’s a two-verse “Dark Star”

that’s not in the same class as the brilliant ones from Europe. NFA > GDTRFB

> NFA burns the house down to complete another evening of Grateful Dead

alchemy.

Following an East Coast tour in

March 1981, the band traveled to London for four concerts before heading on to

West Germany for a show with The Who. These were their first European dates in

seven years. The band would return to Europe for a longer tour in October, and

they would play a second East Coast spring tour in May. It was a hectic year of

travel, especially for Garcia, who was schlepping across America with the Jerry

Garcia Band when the Dead were resting. March 23, 1981, was the third of four

shows in London’s fabulous Rainbow Theater.

A well-played opening set surges

towards the end. Garcia thrills Londoners with his virtuosity during the second

solo of “Sugaree.” On the heels of “Sugaree,” lightning strikes again as Garcia

and mates unload a whirlwind of psychedelic fusion that jolts the Rainbow

Theater during Lazy Lightning > Supplication. This creative song sequencing

continues in set two.

The furious end to the first set was

balanced by a peaceful “Birdsong” liftoff for set two. The instrumental

exploration is long and thorough as Garcia chirps and whistles away as Brent’s

keyboards fill the space between and enrich the aural atmosphere. Effortlessly

shifting gears, the band rocks a thunderous “Samson and Delilah,” and then

Jerry lulls the show back to a dreamlike trance with a gorgeous “To Lay Me

Down,” which was written by Hunter in England ten years earlier. The Garciafest

continues with “Terrapin Station,” and a “Stella Blue” on the “Other One” side

of drums. “Sugar Magnolia” pounds the set to closure, and the show is topped

with a “Casey Jones” encore, a rarity in the ’80s.

One thing that changed during the ’80s,

way before the Dead’s popularity exploded due to their first hit song, “Touch

of Grey,” was the knowledge and passion of their fanbase. When springtime

beckoned, thousands of Deadheads prepared for the ritual of the East Coast

tour. Some of us would make one or two road trips to catch four or five shows,

others would roll with the entire tour. And by 1984, there was an officially

sanctioned taping section, which meant that if you were traveling with a taper,

you’d be listening to that night’s concert on the way home, and if there was

something worthwhile on the tape, your taper friend would dub you a copy of the

show the next day. This underground culture bred incredible passion for the

music, to the point where the shows developed the feel of a religious ceremony.

March 23, 1986 was my 100th Grateful

Dead show, and I knew it would be special, as if somehow, while on stage in the

Philadelphia Spectrum, Garcia would pick up on this vibe and play something to

commemorate the occasion. To a thunderous roar they opened the show with “Gimme

Some Lovin’” and stunned the delirious crowd with “Deal” in the second spot.

During this decade, “Deal” was almost exclusively the last song of the first

set. The crowd knows the band’s every move and they voice raw excitement as

Jerry triggers the big jam. When Garcia starts to peel off some screeching

climactic notes, his devotees respond as one. Now Garcia knows what this crowd

likes and builds an increasingly emotional solo around that motif, and everyone

in the Spectrum goes nuts. It’s a killer jam, especially this early in the set,

and those of us who cherish the tapes know this is a keeper.

Moving on with another unlikely

selection, Weir sings the Dead’s second rendition of “Willie and the Hand

Jive,” a Johnny Otis hit from 1958. The crowd’s delighted, but when Garcia

noodles the tuning of “Candyman,” the Philly Deadheads go bonkers as they

immediately identify the ballad. This is one of those nights where Garcia

savors every line and syllable as much as his devotees. The emotion reaches a

fever pitch on the final verse: “Hand me my old guitar. Pass the whiskey round,

won’t you tell EVERYBODY YOU MEET that the CANDYMAN’S in TOW-OWNN!” Garcia’s

stunning delivery still gives me goose bumps every time I hear it on tape, as

well as hearing the rapturous roar of the crowd.

The relationship between the Dead

and their fans was always unlike any other bond between musicians and fans, and

by 1986, this connection fueled the performances. There was no way a

performance of “Candyman” in 1977 could be as profound and animated as the one

from 3-23-86. Let’s estimate that by 1977 that one-third of a given audience

knew every word of “Candyman.” By 1986, I’d say that three out of every four people

in The Spectrum knew every nuance of “Candyman” and had listened to many more

live versions of the song than the fans from 1977. Deadheads on tour knew these

songs more intimately than folks who regularly went to church or synagogue knew

their prayers. This didn’t make the music better than it was during the Dead’s

prime; however, it gave the Dead’s music a spiritual urgency and a needed boost

on certain nights.

The first set of 3-23-86 also

features spirited performances of “Cassidy” and “West L.A. Fadeaway.” A

transcendent “Comes a Time” brings glory to what otherwise would be just

another solid second set. Garcia digs deep and delivers a moving vocal filled

with compassion, sadness, and hope. It’s a voice of wounded grace as Jerry

croons through a compromised larynx, imbuing this performance with an aura of

heroism. The between-verse solo and the outro jam into “Good Lovin’” match the

emotional texture of the vocal. Garcia’s licks crackle, creak, and croak in a

linear stream.

When “Comes a Time” clicked, it

could give off the illusion of stopping time in its tracks, and the 3-23-86

version possesses that quality, as does the versions from May ’77. Of the

majestic slow numbers that Jerry featured after drums, “Comes a Time” was the

rarest, and my favorite behind “Morning Dew.” After 1986, “Comes a Time” was

only performed seven times. It’s odd because this fit in with the slower-tempo tunes

Jerry favored after his coma. “Comes a Time” was a heartfelt number that was

emotionally draining, and perhaps Jerry didn’t want to run the risk of dragging

it through the mud. March 23, 1986, was my last “Comes a Time.” Gotta make it somehow on the dreams we still

believe.

For more on the other March 23 shows, and other essential dates in GD History, check out:

Deadology